Rock ‘n roll…My life was saved by rock ‘n roll. Forever more I will give it up for The Power & Glory of Rock.

Shortly after the ‘n Roll was dropped from Rock ‘n Roll and long-haired, bearded bands took the stage at open-air festivals, backed by a phalanx of amplification, to play Rock music, these same bands felt the need to get back to rock’s roots. The Beatles got back. The Stones, who’d barely left rock’s roots through their Brian Jones years, wisely ditched the hashish and dashikis and got way back to rural American blues. The Band and Traffic holed up in the countryside. The Byrds went the trad-country route. The rock world called on Sha Na Na to help reclaim that prematurely dropped ‘n Roll. Getting back.

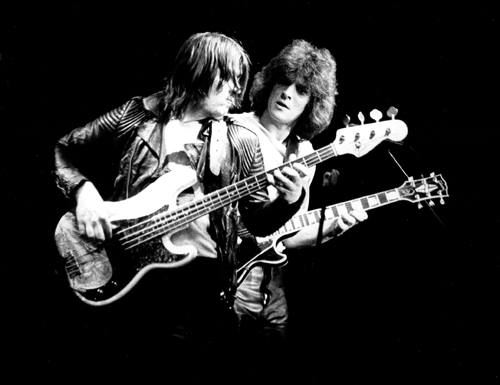

Getting back and joining together, man, in the form of a band! Rock’s Premier Seeker, Pete Townshend, was ripe for rallying behind The Power & Glory of Rock. The Who and The Move, led by eccentric, multi-instrumentalist, conceptualist Roy Wood, applied the thunderous, plodding riffage of their bands to early Rock ‘n Roll’s walking bass lines and pounding piano-driven rhythm sections. Lyrics might commemorate the innocence of early Beach Boys, as The Move did in “California Man” (by this point with Jeff Lynne in the fold, who would continue as a proponent of The Power & Glory of Rock as The Move transformed into ELO) and or celebrate the everlasting Power & Glory of Rock itself, as The Who did so memorably in “Long Live Rock”.

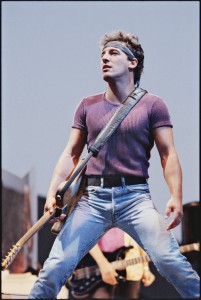

When giving thanks and praise to The Power & Glory of Rock, it’s not enough to sing of innocent times and imagined dance steps, it’s not enough to restore the slightly frantic, swinging rhythms that marked the genre’s explosion onto the pop culture landscape. No, every shred of humanity in each riff and downbeat must be thrust to the fore, revived, exploited. The song becomes secondary. The act of getting back becomes secondary. Rather, it is the act of giving thanks and praise itself that comes to represent The Power & Glory of Rock.