Robyn Hitchcock & The Venus 3‘s Propellor Time is an understated release that was recorded, mostly live, in a week’s time in 2006, between the recordings for two prior Venus 3 releases, Ole Tarantula! and Goodnight Oslo. Never having been the world’s greatest Robyn Hitchcock fan, I can’t be sure of the pulse of his fans today, but if anyone’s expecting a collection of jangly songs about the sexual lives of insects and fishes, prepare for a letdown.

Hitchcock does not abandon his silly, creepy crawly motifs, such as the verse in “Afterlife” that describes the monarch butterfly’s secretion of “royal jelly,” but he seems more willing than usual to scratch beneath the surface, to the true themes of his work – love, sex, death, and all that good stuff – and address them directly. In “Star of Venus” he provides the image of a skeletal couple driving well beyond the point when death has done them part, the man’s arm around his wife’s shoulders: “And that’s true love,” he sings, “they’ve still got the radio on.” It’s a sweet image that he resists spraying with 10cc of jelly.

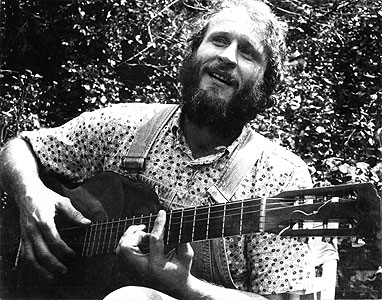

Robyn Hitchcock & The Venus 3, “Star of Venus”

For years Hitchcock played in trios and jangly quartets that had the musical range of his jangly trio: high end to higher end. I’ve got a nasty, thoroughly unfair theory about musicians who spend too much time leading trios: with the exception of an unmatched talent like Jimi Hendrix, it tells me the bandleader does not play well with others. This is what I figured was the case with Hitchcock until the mid-’90s, when Young Fresh Fellows mastermind Scott McCaughey (who also serves in the Oliver role for REM) recruited Hitchcock to be part of the pop collective The Minus 5. McCaughey and the other American, Minus 5 collaborators who make up The Venus 3, Peter Buck and Bill Rieflin, help Hitchcock swim with the current rather than against it. Propellor Time is loaded with other cool contributors, who sound like they’ve simply “dropped in”: Nick Lowe, John Paul Jones, Chris Ballew, Morris Windsor, and Johnny Marr, among others.

Perhaps Hitchcock’s been getting to the heart of the matter for a lot longer than I’ve paid attention – sorry, Robyn, if that’s the case – but with one exception whenever I revisit the albums Hitchcock released in the ’80s and ’90s I quickly recoil from the dimestore Syd-isms and sophomoric, cosmic observations. Sonically, the high-end jangle of his band-oriented albums never helped, and for some reason it felt to me like he was laying on the British accent a little thicker than necessary.

Element of Light has always been the exception for me. Hitchcock isn’t so nervy, sly, and hectoring. The music is more lush. He makes more references to John Lennon than Syd Barrett, and with the richer-than-usual backing tracks his multi-tracked vocals sit atop the mix like Brian Eno. I can listen to tracks like “Winchester” and the funny/sad “Ted, Woody, and Junior” a half dozen times a day – and often I do.

From an interview on his website, Hitchcock mentioned that he couldn’t have made this album 10 years earlier:

I didn’t have the stew of people, or the philosophy in the songs. Perhaps I had the wrong kind of wisdom then. You lose speed and you gain depth.

No wonder I like about this album more than most Robyn Hitchcock albums I’ve bought. He’s got a supportive stew of friends who keep him from rushing ahead and offering glib, shorthand observations on the order of the cosmos. As with Element of Light, there’s more Lennon at the heart of this album than Syd, and a little Dylan. If you’ve lived this long you can aspire to Lennon and Dylan. Syd was fantastic in his own way, but he’s a dead-end. Maybe Hitchcock has figured this out. “We love you, sickie-boy,” he and his sickie friends sing toward the end of an album, rallying around each other – and us.